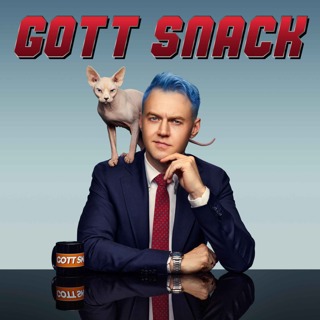

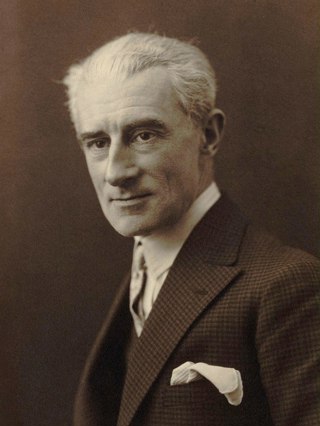

Ravel, Bolero + La Valse

Maurice Ravel the Magician, the Swiss Watchmaker, the aloof, the elegant, the precise, the soulful, the childlike, the naive, the warm, the radical, the progressive. These are all words that were used to describe a man of elegant contradictions throughout his life and into today. I talked a lot about Ravel's skill with orchestration last week when we discussed Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, but Ravel's brilliance and creativity in terms of orchestral sound is absolutely unparalleled in musical history. But Ravel is somebody I've very rarely covered on the show, partly because he didn't write very many large scale works that would cover a whole hour long episode. Well, it took 6 years for me to figure it out, but I realized a little while ago that I could cover two of Ravel's shorter pieces and put them together on a double bill, so to speak. So today I'm going to tell you about Ravel's most beloved and most despised piece, Bolero, and about my favorite piece of Ravel's, La Valse. These are two pieces that could not be more different in their aims, in their constructions, and in their impacts on the audience. They are both thrillingly exciting, but in completely different ways. A good performance of Bolero should make you want to jump out of your seat with excitement, while a good performance of La Valse should terrify you to your core. Join us to learn all about it!

22 Juni 202354min

Mussorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition

Have you ever been to an art museum and wished that you had music to accompany your experience? Music that made the art you were looking at more vivid, more immediate, and more emotionally intense? Well, Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition is the piece for you. Inspired by his late friend Victor Hartmann's paintings and designs, Mussorgsky composed a series of 10 miniature pieces for piano based on Hartmann's works. Unlike many other collections of miniature pieces that have thematic or structural connections, Pictures at An Exhibition doesn't feature that at all, keeping with Mussorgsky's often rebellious ways as a composer. Instead, the music is connected by movements called Promenades, as if Mussorgsky literally walks you to the next painting at the exhibition. Mussorgsky's remarkably imaginative piece is justly famous and often played by pianists, but what is perhaps the most fascinating thing about this piece is the creativity that it has inspired in other composers. Pictures at an Exhibition, or parts of it, has been arranged more than 50 times for any number of configurations of musicians. So today, we're going to explore each picture in detail, talking about what Mussorgsky actually does to make these works of art come to life in such a compelling way. At the same time, we're going to compare the original piano piece to some of the arrangements, focusing of course on the most famous of them all, the explosion of color that is Maurice Ravel's arrangement. We'll also talk about Mussorgsky himself, his compositional reputation at the time, and the brilliant creativity of this one of a kind piece.

15 Juni 202358min

Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4

Welcome to episode number 200 of Sticky Notes!! On December 22nd, 1808, a day that would live in classical music lore forever, Ludwig Van Beethoven sat down for his very last appearance as a solo pianist to play this new piano concerto, his 4th. This performance was not only the premiere of the new piano concerto, but the premiere of two new symphonies as well, the 5th and the 6th. It featured many other new works, and the concert itself lasted nearly 4 hours, all inside of the cold and dark Theater an Der Wien with an underprepared and underrehearsed orchestra. The concert, despite featuring 3 works that would go on to be some of the most performed works in the history of classical music, was not a success. It was too long and too cold, featuring too many premieres and too much difficult music. It was criticized severely in all quarters, and Beethoven considered the concert a failure. And even that new concerto, the one that surprised so many people with its supremely gentle character, didn't catch on quickly at all. It wasn't until 1836 when Felix Mendelssohn, who we have to thank for so many of these situations, revived the piece. Today it is known as one of the most beloved concertos in the entire piano repertoire, partly due to the fact that it is so surprising, but not for the reasons one normally would expect. In the 4th piano concerto, Beethoven turns his entire musical brand so to speak upside down. Instead of a blazing fire, we get a gentle warmth, instead of drama, we get tenderness. And instead of virtuosity, we get a practically transcendental level of simplicity. Other than the short second movement, which does give us some of the old Beethoven fire, it is one of the most tender creations of Beethoven's entire career. Join us to learn all about it today!

8 Juni 202359min

Shostakovich String Quartet No. 8

What did Dmitri Shostakovich intend to portray in his music? There is probably no more debated a question in all of 20th century Western Classica lMusic than this one. On the surface, it seems to have an easy answer. Shostakovich portrayed his own thoughts and feelings in his music, just as any other composer would. And that is certainly true. Shostakovich, above anything else, was truly one of the great composers in history. HIs mastery of form, meldoy, strcuture, pacing, and his ability to find a near universal expression of grief and passion is practically unparalelled among composers. That much is clear to those of us who love Shostakovich's music. But everything else, including that thorny question of what his music MEANS, is much, much, much less clear. Practically Shostakovich's entire life was lived under the shadow of Soviet Russia, and naturally his musical career was lived under that shadow as well. This means that a sometimes impenetrable layer of secrecy, mystery, and doubt always lies under the surface of Shostakovich's music. In 1960, Kruschev, who had been loudly trumpetting Shostakovich's name to Western Press as an example of a free Soviet artist post the excesses of the Stalin regime, decided that Shostakovich should be the new head of the Russian Union of Composers. The catch was that Shostakovich would need to join the Communist Party in order to take the job. Shostakovich, who had long resisted becoming a full Party member, agreed. Shostakovich was clearly disappointed in himself, as his friend Lev Lebedinsky wrote this: "I will never forget some of the things he said that night [before his induction into the Party], sobbing hysterically: 'I'm scared to death of them.' Why does all this matter? Because just a few days after joining the Commhnist party and after meeting with his friends Isaac Glikman and Lev Lebedinsky, Shostakovich traveled to East Germany -- specifically to Dresden — to work on a film which would commemorate the destruction of the city during World War II. He was supposed to write music for this film, but instead, Shostakovich sat down, and in THREE DAYS, he wrote his 8th string quartet. He would later write to Glikman: "However much I've tried to draft my obligations for the film, I just couldn't do it. Instead I wrote an ideologically deficient quartet that nobody needs. I reflected that if I die it's not likely anyone will write a quartet dedicated to my memory. So I decided to write it myself. You could even write on the cover: 'Dedicated to the memory of the composer of this quartet." Today on the show we're going to explore this remarkable piece together - join us!

1 Juni 202350min

What Does a Conductor Really Do?

Have you ever wondered what it is that us conductors are really doing up there? Are we just waving our arms in time to the music? What role does the conductor actually play in a concert? How about a rehearsal? Do we also learn to be train conductors as well? Well, today's episode is about answering those questions! We'll talk about conducting on 3 different levels, including the basic level where we'll talk all about beat patterns, studying, rehearsals, concert programming, and more. We'll also talk about what I like to call the 30,000 feet level, where all of those basic decisions can help translate into musical ideas that inspire the orchestra and move the audience. And finally, we'll head to what the late great conductor Mariss Jansons called the Cosmic level, where true inspiration takes place. This can happen as little as once or twice in a lifetime in a concert, but when it does, there is nothing like it! We'll talk about all this, and more today - join us!

25 Maj 202347min

All things Piano with Marc-André Hamelin

Marc-André Hamelin is one of the world's greatest living pianists. He is known as a virtuoso of the highest order and has made nearly 100 recordings spanning the gamut of the piano repertoire. In this conversation we talk about how Marc fell in love with Gershwin, piano rolls, Busoni, Godowsky, the nature of virutosity, Haydn, CPE Bach, programming, nerves on stage, and much much more! This was such a fun and wide-ranging conversation and I certainly learned a lot speaking with Marc about the piano. Join us!!

18 Maj 202352min

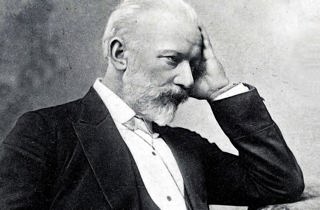

Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4

"This is Fate, the force of destiny, which ever prevents our pursuit of happiness from reaching its goal, which jealously stands watch lest our peace and well-being be full and cloudless, which hangs like the sword of Damocles over our heads and constantly, ceaselessly poisons our souls." With this description, Tchaikovsky gave his patron Nadezhda von Meck a rare insight into the inspiration behind what he called the "nucleus" of his 4th symphony. Despite the fact that Tchaikovsky's music is famously emotional, he usually did not like describing his programs using words. This is one of the contradiction of Tchaikovsky's music for the modern listener: we have these letters where Tchaikovsky described the programs or stories behind many of his most famous pieces, and yet Tchaikovsky himself would not have necessarily wanted us to know them. Tchaikovsky's 4th symphony is at the center of all of these contradictions. It is a symphony in the grand Romantic tradition of the symphony, with all of the technical trappings that a symphony requires. It is also a piece that reflects the growing trend at that time towards symphonic poems, especially in the massive first movement. It is also a piece that seems to be inspired directly by two events in Tchaikovsky's life, his disastrous marriage, and his unique correspondence with Nadezhda Von Meck, his patron who he corresponded with for 13 years without ever meeting her. This relationship was at its beginning when Tchaikovsky wrote this symphony, and so strong were his feelings of companionship with her that he often wrote that this 4th symphony was not "my symphony" but "our symphony." So today we're going to go through this symphony on two levels, the technical, explaining all of what makes this symphony so tragic, powerful, exciting, and beloved, and also the historical, going into Tchaikovsky's marriage to Antonina Miliukova, and his relationship with Nadezhda von Meck. We'll also talk about the reception to this symphony, which, well, let's just say it was anything but positive. Join us!

11 Maj 20231h

My 25 Favorite Moments in Classical Music (Part 2)

Last week we covered moments 1-15 in my top 25 favorite moments in classical music, going all the way up towards the end of the 19th century. This week we're going to explore 9 of my favorite moments from the wide world of 20th century music, and then, in a little twist, I'm going to look at 5 of my favorite moments from living composers. We're going to hear from Stravinsky, Mahler, Dawson, Barber, Shaw, Gruber, Widmann, Scriabin, Shostakovich, Debussy, Ravel, Chin, Skye, and more this week so join us to hear some amazing classical music moments!

4 Maj 202355min