Impressions in Blue: Ravel & Gershwin

In the mid-1920s, Maurice Ravel wrote a letter to the legendary composition teacher Nadia Boulanger. Boulanger's class was a mecca for composers, both young and old, and musicians from all over the world vied to study with her. But Ravel's letter wasn't on his own behalf. Instead, he urged Boulanger to take on a young student whom Ravel himself had declined to teach. He wrote: "There is a musician here endowed with the most brilliant, most enchanting, and perhaps the most profound talent: George Gershwin. His worldwide success no longer satisfies him, for he is aiming higher. He knows that he lacks the technical means to achieve his goal. In teaching him those means, one might ruin his talent. Would you have the courage, which I wouldn't dare have, to undertake this awesome responsibility?" Boulanger also declined to take Gershwin as a student, fearing, like Ravel, that she might damage his spontaneity and dynamic jazz sensibility. Whether or not the famous story is true (that Ravel turned down Gershwin's request to study with him by saying, "Why be a second-rate Ravel when you are a first-rate Gershwin?") we may never know. But the two composers were friendly, and formed something of a mutual admiration society. Today, in this fourth collaboration with G. Henle Publishers in honor of their Ravel and Friends project, we're going to explore the connections between these two great composers: their friendship, their mutual influence, and the profound ways jazz infused itself into Ravel's music, particularly in his Violin Sonata and Piano Concerto in G. From the moment he discovered it, Ravel adored jazz, and like many French composers of the time, allowed its influence to permeate his work in ways both explicit and subtle. Join us!

7 Aug 44min

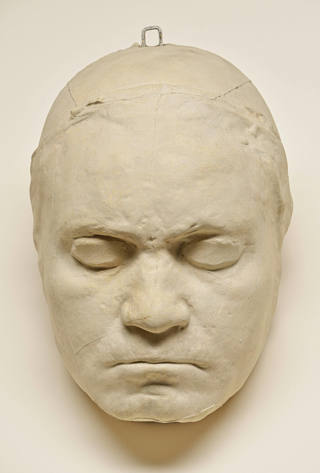

Beethoven Piano Sonata in B Flat Major, Op. 106, "Hammerklavier" - Part 2

There is a special category when it comes to Beethoven; a catalogue that doesn't include complete symphonies, sonatas, concerti, string quartets, etc., but just single movements. This is the catalogue of great Beethoven slow movements. Beethoven's slow movements are like a great Tolstoy novel. They span the gamut of human experience and also reach beyond it, into something we cannot understand but all somehow perceive. Simply put, Beethoven often seems to know us better than we know ourselves. This brings me to the slow movement of Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata. Unlike those late quartet slow movements, the slow movement of the Hammerklavier is not about ecstatic contemplation. Instead, it is a movement of pure and profound despair. It has been described as "a mausoleum of the collective suffering of the world," and "the apotheosis of pain, of that deep sorrow for which there is no remedy, and which finds expression not in passionate outpourings, but in the immeasurable stillness of utter woe." This is not a movement I would necessarily enter into lightly as you go about your day—it requires you to take a moment and enter a world unlike any other. Today, in Part 2 of this Patreon-sponsored exploration of this great, in all senses of the word, Sonata, we'll go through this slow movement in detail. Then we'll tackle the life-affirming and maddeningly complex last movement, which is not quite the antidote to the slow movement, but perhaps it is the only possible answer to the questions the third movement so profoundly asks. Join us!

24 Juli 53min

Beethoven Piano Sonata in B♭ major, Op. 106, "Hammerklavier" - Part 1

Beethoven once wrote to his publisher: "What is difficult, is also beautiful, good, great, and so forth. Hence everyone will realize that this is the most lavish praise that can be bestowed, since what is difficult makes one sweat." If this credo manifests itself most powerfully in any one of Beethoven's works, it might be the piece we'll talk about today, the piano Sonata Op. 106, nicknamed, "Hammerklavier." It is the longest Sonata Beethoven ever wrote, which essentially means that it was the longest sonata anyone had written up to that point. It marks one of the pivot points between Beethoven's so-called heroic period and his late period, where his music became even more cosmically beautiful than before. It is certainly his most ambitious Sonata to that point, and his most difficult. The scale of the Hammerklavier sonata is hard to describe; in around 45 minutes of music, Beethoven explores the full gamut of human emotion. The intensity, the difficulty, and the concentration that this sonata requires from the pianist and listener alike has led to many people, as the pianist Andras Schiff says, to "respect and revere this Sonata, but not love it." Most of the articles and analyses of this sonata that I found in researching this show emphasize its difficulty, its scale, its obsessiveness, and its impenetrability. But I must say that when I talk to musicians abut this piece, their eyes light up. Yes, this sonata is difficult, but what have we just learned from Beethoven? What is difficult is also beautiful, good, great and so forth. Join us as we begin a two part exploration of this remarkable work together. Thank you to Jerry for sponsoring this show on Patreon! Recording: https://youtu.be/yBtJF_4msqw?si=bIznKSGuRyXDbFaT

10 Juli 44min

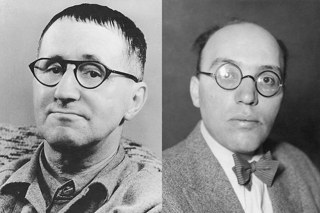

Weill: The Seven Deadly Sins

The collaboration between Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht is rightly legendary. The two men could not have been more different from each other, and like the Brahms/Joachim relationship I mentioned in my recent show about the Brahms Double concerto, the friendship between Weill and Brecht was stormy to say the least. The two collaborated on some of the most memorable works of the Weimar era in Germany, such as the Threepenny Opera, which features a pretty famous tune called Mack the Knife. Their final collaboration was on the "sung ballet" The Seven Deadly Sins. This is a piece that was written at a point of remarkably high tension within Weimar Germany. On an artistic level, the 1920s and early 1930s had seen a veritable explosion in the world of culture, with art, dance, theater, and music all featuring artists who were pushing the boundaries with wild experimentation and a kind of ecstatic fervor that produced some of the world's greatest and most memorable cultural achievements. On a parallel track however, the rise of the Nazis cast a pall over all of this. By 1933, both Brecht and Weill(who was Jewish) knew that Germany was not a place that they could stay safely. Weill ended up in Paris and then in the US for the rest of his life, while Brecht bounced around Europe before returning to East Germany after the war, hoping to be a part of the Marxist Utopia that he believed had been founded there. The simmering combination of Weill's mastery of transforming popular forms into a unique kind of classical music along with Brecht's pointed satire and brilliantly inventive libretti resulted in the Seven Deadly Sins, a piece that that brutally satirizes extreme capitalism and the degradation of the human soul that supposedly results from it. This is a nakedly political piece, and I should make it clear that by talking about it, by choosing to feature it on the show, and by regularly performing it, I don't necessarily endorse its views. Brecht was extreme in all ways, as we'll get to today, and the power of this piece in my opinion doesn't come from its politics, but from its remarkable and devastating portrayal of a human soul and the tragedies that can befall it. This is one of my favorite pieces of the whole 20th century, and I'm so happy to share it with you today. Join us!

26 Juni 1h

The Ravel Sound with Norbert Müllemann and Stefan Knüpfer

I so enjoyed making this latest episode in my collaboration with G Henle Publishers. I talked with two absolute experts in their fields, Norbert Mülleman and Stefan Knüpfer, all about how to edit Ravel's music, and how to create the Ravel sound on the piano. This episode definitely veers into some very nerdy territory, but Norbert and Stefan are both so brilliant at explaining very high level concepts in a way that anyone can understand, from a person who has never looked at a score to a professional performer. I think everyone will learn a lot from this episode and I don't think you'll ever hear Ravel the same way again after listening! Enjoy!

12 Juni 45min

Dvorak Violin Concerto

Admit it: if you're a fan of classical music—or even just a regular concertgoer—you might have glanced at the title of this episode and done a double take. The Dvořák Violin Concerto? Not the Cello Concerto? One of the things I love about my job as a conductor—and my side gig as a podcast host—is bringing audiences and listeners like you pieces you may never have heard before, even if they're by extremely well-known composers. Don't get me wrong, I love the blockbusters. But there's a special thrill in introducing someone to something new. Now, some of you might already be big fans of the Dvořák Violin Concerto. But in my experience, it's relatively unknown compared to Dvořák's more famous works. I've never performed it myself, and I've only heard it live once. It's not part of most touring soloists' repertoire, and it's just one of those pieces that rarely comes up—especially compared to the Cello Concerto, which I think I've conducted at least once every season since becoming a conductor. This concerto came about much like the Brahms Violin Concerto, the Brahms Double Concerto we talked about a couple of weeks ago, and so many other great 19th-century works: inspired by the sound of Joseph Joachim's violin. Joachim was the great violinist of the 19th century and had been a friend and supporter of Dvořák for many years. Dvořák ended up dedicating the concerto to Joachim, writing: "I dedicate this work to the great Maestro Jos. Joachim, with the deepest respect, Ant. Dvořák." Sadly—and for reasons that remain somewhat unclear—Joachim never performed the piece. That may be one of the reasons it's never achieved the popularity it deserves. Today, in this Patreon-sponsored episode, we'll dive into the concerto, exploring its unusual form, the myriad challenges it poses for the violinist, and perhaps some reasons why it's not part of the so-called "Big Five" violin concertos—even though it probably deserves to be.

29 Maj 49min

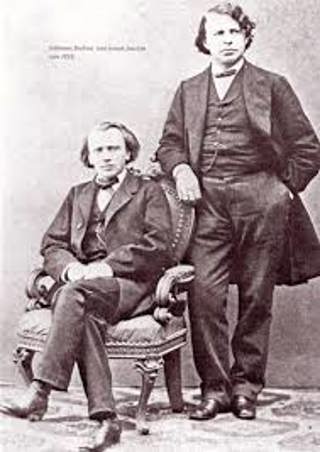

Brahms Double Concerto

It's entirely possible that we would not know the name of Johannes Brahms very well if Brahms hadn't met Joseph Joachim as a very young man. Joachim, who was one of the greatest violinists of all time, had already established himself as touring soloist and recitalist, and he happened to know the musical power couple of Robert and Clara Schumann quite well. Joachim encouraged Brahms to go to Dusseldorf to meet the Schumann's, and the rest is history. I've talked about the Brahms-Schumann relationship dozens of times on the show before, but to keep it very brief, Robert Schumann's rhapsodic article Neue Bahnen(new paths) launched Brahms' career, and until Schumann's deterioration from mental illness he acted as a valued friend and mentor for Brahms. Clara Schumann, as a performer, was a powerful advocate for Brahms' music as well as a devoted and loving friend throughout the rest of their lives. Almost constantly present in this relationship was the sound of Joseph Joachim's violin. Brahms did not have a huge circle of friends, but for the often difficult to get along with composer, Joachim was a musical and spiritual companion. Brahms' legendary violin concerto was written for him, and the two collaborated closely for the entire course of their musical lives, except for one significant break. Brahms and Joachim were estranged for 7 years, until Brahms reached out with a remarkable conciliatory gesture: a concerto for Violin and Cello and that would be dedicated to Joachim. Brahms and Joachim(as well as Brahms and Clara Schumann) had often resolved disputes through music, and this was no exception. Clara Schumann gleefully wrote in her diary after Joachim had read through the piece with cellist Robert Hausmann: "This concerto is a work of reconciliation - Joachim and Brahms have spoken to each other again for the first time in years." One would expect that a work like this would be beloved, but the Double Concerto has had a checkered history, which we'll also get into later. Clara herself wrote that it lacked "the warmth and freshness which are so often found to be in his works," It would turn out to be Brahms' last work for orchestra, and one of the few in his later style, which makes It fascinating to look at from a compositional perspective. Partly because of the cool reception it got in its first few performances, and the practical challenges of finding two spectacular soloists who can meet its challenges, the piece is not performed all that often, though I have always adored this piece and am very grateful to Avi who sponsored this week's show from my fundraiser last year before the US election. So let's dive into this gorgeous concerto, discussing the reasons for Joachim and Brahms' break, their reconciliation, the reception this piece got, and then of course, the music itself! Join us!

15 Maj 58min

Copland Clarinet Concerto

The commission for a new Clarinet Concerto from the great American composer Aaron Copland came from a rather unlikely source: Benny Goodman, the man known as the King of Swing. Goodman was one of the most famous and important jazz musicians of all time, but in the late 1940s, swing music was on the decline, and bebop had taken over. Goodman experimented with bebop for a time but never fully took to it in the way that he had so mastered swing. Goodman then turned towards the classical repertoire, commissioning music from many of the great composers of the time, such as Bela Bartok, Darius Milhaud, Paul Hindemith, Francis Poulenc, and of course, Aaron Copland. Copland eagerly agreed to the commission, and spent the next year carefully crafting the concerto, which is full of influences from Jazz as well as from Latin American music, perhaps inspired by the four months Copland spent in Latin America while writing the piece. What resulted from all this was a short and compact piece in one continuous movement split into two parts. With an orchestra of only strings, piano, harp, and solo clarinet, Copland created one of the great solo masterpieces of the 20th century. It practically distills everything that makes Copland so great into just 18 minutes of music. Today on the show we'll talk about the difficulty of the piece, something that prevented Benny Goodman from performing the concerto for nearly 2 years, as well as the immense difficulty of the second movement for the orchestra. We'll also talk about all of those quintessentially Copland traits that make his music so wonderful to listen to, and the path this concerto takes from beautiful openness to jazzy fire. Join Us! Recording: Martin Frost with the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra Pedro Henrique Alliprandini dissertation: https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/alliprandini_pedro_h_201812_dma.pdf

1 Maj 48min